Hitherto, I've always contented myself with a cruise reasonably close to up the Hudson to Albany, again down to Hatteras, or up to Martha’s Vineyard. But this year I wanted to see the World's Fair in Chicago and I wanted to cruise. So I decided to make it a whale of a vacation by driving my Elto-powered Old Ironsides to Chicago.

My business is at its quietest from about August first to the middle of September. Also wind and weather on our interior waterways are probably as favorable at this time as any. Accordingly, I planned to start for Chicago about August first.

I was a little puzzled as to the route to take. Naturally, the long route southward around Florida and up the Mississippi-Illinois waterway was out on account of the time element; also because of the approach of the hurricane season.

Two other routes were feasible. Both followed the Atlantic Coast, Hudson River, Erie Canal as far as Three River Point in New York. One route then follows the Canal west to Lake Erie at Buffalo—then Lake Erie to the Detroit River, Lake Huron, and down Lake Michigan to Chicago. The second and chosen route follows the barge canal north to Oswego, across Lake Ontario to Trenton, via Trent Waterways to Midland, Georgian Bay, North Channel and Lake Michigan.

The latter route was chosen, first because I felt it would take me through far more beautiful country which would in turn make my trip the more enjoyable; secondly, because it offered the shorter and more protected route for my small craft. Now that it’s over, I know I made no mistake, for every foot of the way offered new and magnificent views that I'm sure could not be found on any other route.

Now as to equipment, there was little of it. I have found that the tendency is always to over-equip, and of the two, I really believe the water traveler can make faster time under-equipped than he can if he has to wrangle a deck load of knickknacks that he thinks he may

have use for.

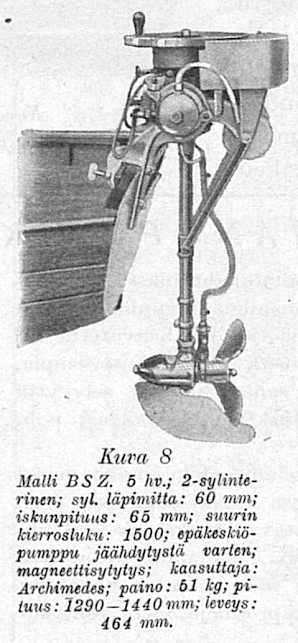

The motor was a hand-starting 1933 Elto Super C, which developed 21.2 N.O.A. certified B.H.P. I have used this model for three years for my own cruising as I have found it to contain just the right balance of power, speed, and ruggedness for all around work. In the 1800 miles which I travelled on this cruise the only motor replacements made were shear pins. When I arrived at Milwaukee on the way to Chicago, I had the motor checked at the factory and found that not a single part needed replacing.

Before going in the water, without equipment the boat weighed 520 pounds. Total weight

including all equipment, spare gas, myself (I weigh 200 pounds), and motor, was 1100 pounds. Completely loaded, it had a cruising speed of 25 m.p.h., a top speed of 28 m.p.h. The same outfit minus only miscellaneous equipment, which ran about 300 pounds, made a certified American Power Boat Association record of 33 miles per hour with a strictly stock Elto Super C.

I used no auxiliary fuel pumping system as this would mean extra weight and would take up valuable space. I much prefer to run out a motor tankfull, stop and refill out of a 5-gallon can. This afforded a regular opportunity to stretch, relax, and take bearings. Then too, refilling this way even in rough water wasn't hard, as my boat rode even a good chop very nicely.

I also carried a good barometer, two magnetic compasses, one costing 35 cents, the other

75 cents, a chart roll, five 5-gallon gas cans, a couple of tins of corn willy and ships biscuits,

a couple of cans of beans, tea, a can of Sterno, a gallon water canteen, a paddle, a small mast and sail (never used), a few spare parts (never used), a Navy bed roll, a suit of shore-going clothes, and the full Navy complement of underwear, toilet articles, etc.

The need for compasses is self-evident. The barometer was equally necessary, for by regular

reference to that, particularly in the Great Lakes region where I was not acquainted with the

fresh water weather whims, I was able several times to find cover in advance of sharp squalls

which sprang up unannounced, except by the barometer. I could have ridden them out all

right, but seven years of U.S. Navy experience taught me never to hunt trouble with the weather.

The above equipment, with the exception of spare clothing, is in my boat all of the time so that preparing for a 2,000-mile trip never takes more than ten minutes.

As I stated, I wanted to start about August first, but with a perversity usual in such cases,

business suddenly picked up the latter half of July and seemed bent on keeping me at home. I stood it as best I could until August third. That day was very busy, but about 4:30 in the afternoon, things let up a little. There were no appointments for tomorrow. So I closed my desk, turned the place over to my assistant, and left.

I took on ten gallons of gas, and at 5:05 P.M. I was leaving Atlantic City. As I was leaving my dock, my assistant dashed down to the dock, waving what looked like a telegram, and shouting. With a hurried admonition to him to handle whatever it was himself, I resolutely closed my ears and turned my back. The cruise was on.

I didn’t get far the first night. Shortly after 6:30 after having made about 35 miles, I noted a mean-looking thunder squall making up in the northwest. Open salt water is no place to be in a thunder storm, so I turned into Barnegat Harbor and stopped for the night. It was well

I did for the squall turned out to be a hard storm of wind and rain.

I left Barnegat early the next day and cruised up the bay. I got as far as Manasquan Inlet at

11:00 but the ocean was too rough so I put up at Brielle, New Jersey, for the rest of the day.

August fifth I left Brielle at 7:34 A.M. The sea was heavy and rolling, but seemed to be calming down. Even now I couldn’t avoid business entirely, for about 10:00 A.M. I was hailed by the fishing boat Mi-Lad which was unable to run on account of ignition difficulties. I sold them a battery for auxiliary ignition.

About noon the next day I left Poughkeepsie. The morning was somewhat foggy and anyhow I was in no hurry. I wanted clear weather to run the bars and snags of the Hudson. I made fair time going up and finally tied up for the night at the Albany Yacht Club.

A drizzling rain greeted me the next morning, and as this was a pleasure trip and I dislike traveling in rain, I delayed shoving off until 11:30 A.M. when it cleared. Now began one of the prettiest portions of the trip. High, green hills all around, millions of varicolored wild flowers, picturesque homesteads—truly a beautiful country.

About noon I waved to a New York Central freight train. The flagman’s hand waved 10-20-30, meaning I was doing 30 m.p.h.

Good traveling, but easy in the smooth canal.

At Lock No. 21 I was locked through with a large tanker loaded with molasses, and here

incidentally, my cruise came close to ending. I was laid up alongside the tanker and the

lock started to fill. I suddenly noticed the great side of the larger ship moving toward me.

A loose forward mooring line was the cause as I later found.

I shouted but the din of machinery and rushing water drowned me out. I didn’t have time to paddle out, and anyhow the paddle was inside my little cabin. Fortunately, I had left the starting rope coiled around the flywheel. I gave it a hard yank. The motor caught and I chugged out of the way. Not any too soon, either, for sidewise progress of the tanker wasn’t halted until it was within a couple of feet of the lock wall. I wouldn't have been hurt, but my boat would have been crushed. After that when going through locks with larger boats, I stayed under either the bow or stern.

My bed was soft and hard to leave next morning so it was after eight August ninth before I started across Lake Oneida. This is a beautiful body of water, 20 miles long by about 5 miles wide. The land surrounding the lake is rugged in character and adds much to the attractiveness of the lake.

Forty-five minutes sufficed for the run across Oneida. About midway through the lake, I passed thousands of dead whitefish. I couldn’t ascertain the cause of this, but some people in Brewerton at the west end of the lake, told me that this occurred every few years.

The canal from Brewerton to Phoenix must be a campers’ paradise for I passed hundreds of them here. I don’t blame them, they've got high ground, beautiful scenery, good water—in fact, about everything a camp should have.

This day I also stopped at Phoenix and went through a paper mill with E. O. Krom. I had never seen paper made before, and it was tremendously interesting. The barge canal has a great many small manufacturing plants along it that would be well worth the traveler's time to investigate.

Finally, I reached Oswego on Lake Ontario. Not a bad day’s run—considering the many locks and dams I had to pass. In fact, I found myself well satisfied with progress made. In five days of leisurely travel I had come from Atlantic City clear across New York through dozens of locks, and still I hadn't hurried but had staved in unless the weather was good. This was a pleasure trip, not a speed contest.

The next day, Thursday, brought a stiff southeast wind. I ventured out twice but found the lake too rough for comfortable traveling so I stayed in Oswego.

Friday brought an increasing wind but upon being told by a local prophet that this wind was apt to hold for three or four days longer, I decided to push on. Early in the afternoon I left with the wind still freshening a bit from the southeast. I laid a somewhat roundabout course, heading north for the first three hours, then west. It was very bumpy and of course I did not attempt to travel full throttle but was content to keep the boat just in a planing position.

The morning of August twelfth was spent passing customs and getting a permit to enter Canada and the Trent Canal, and cleaning up my boat and motor. By noon everything was set and sharply at 12:00 I pulled out. Passed through I don’t know how many locks but it seemed like hundreds. I finally arrived at Hastings, an old vacation town, at dusk. This is a typical resort town, almost deserted in winter, they told me, but quite lively with resorters in summer.

August 13, 14, 15 and 16, passed in running the Trent Canal with its many lakes. At the time thought, ‘Here is surely the boater's paradise!” Rough wooded hills, rocky hills, deep canyons, waterfalls, large and small, high and low, numerous lakes of all sizes studded with hundreds of beautiful green, little islands—all making scenery that will compare with the best found anywhere. I took my time stopping whenever the spirit moved me, exploring

now and then, in short, thoroughly enjoying myself. As a matter of fact, I forgot to eat for a time.

So contented was I with what I had seen that I felt supper wasn't worthwhile so I turned in and slept in the boat that night. The next morning I woke at 5:00 A.M. and not wanting to wait until the town folks got up, and being anxious to get into Lake Simcoe, which I was told was more beautiful than the rest, I decided to let breakfast go until noon.

I found this photo of the boarding house in this article at http://parkscanadahistory.com/series/ha/40.pdfat

The nineteenth saw the weather clear and the barometer rising so at 9 o'clock I laid a northeast course and started up Georgian Bay. RIGHT here I want to recommend that you do not attempt to buy charts of Canadian waters in any of the smaller Canadian towns.

Such charts as I could get were old and the ones I bought in Midland were dated 1908. They were very incomplete. Get them in Toronto or some other large place.

On the other hand, the small towns can't be blamed too much for Georgian Bay has fallen 8 feet in the last ten years and many charts up to date in 1920 are useless now.

I soon found out how incomplete the charts were. About 11 o'clock I landed on a good sized

island and nary a trace of it could I find on the chart. The mainland shoreline zigged where the chart said 1t should zag, so all in all I was puzzled. That's where a man who hasn’t done much navigating is better off than the fellow who travels by chart and compass. The greenhorn will barge ahead in the general direction and nine times out of ten will come out O.K. The navigator is afraid of the tenth time, however, and stays put until forced out or shown the way.

I hailed a couple of passing boats but they were no better off than I. So I settled down to wait until someone who knew the channels came along. Fortunately, this turned out to be only an hour. The cruiser Clivea, of Toronto, came along and graciously gave me permission to follow them. Also they handed me two of the nicest sandwiches I have ever eaten.

We arrived at Parry Sound soon after 2 and there I found an easy solution for future navigation troubles—an Indian guide. I picked up Dave Parwis, an Ojibway Indian and in exchange for his guidance, carried him to Ojibway. That run takes the local steamer five hours. We made it in an hour and forty minutes. Dave said it was the fastest boat ride he ever had.

From Ojibway to Pointe au Baril is miles of water and rocks—mostly rocks. I made it in eight minutes with a Mr. F. Massier as guide. I camped for the night at the Bellevere Hotel, well satisfied with the day's run of 100 miles through rocks and water.

Monday morning I left Point au Baril quite early and headed out into the bay and deep water. I much preferred to stay in close to shore for the barometer had been jumpy for a couple of days and seemed to promise heavy weather rather than otherwise. However, I didn't want to pile up on some rock just under the surface so I struck into the bay.

This was a trying and at the same time an inspiring day. I ran from Pont au Baril to Drummond Island, Michigan, through the grandest cruising country in the world. For elemental grandeur nothing excels it. There are great ridges of bare granite that still show the deep scars which the great glacier put there just before the dawn of written history.

That night was cold and as there was no human habitation in sight I stayed in the boat again. I brought out my can of Sterno and put it to work. I heated some beans, corn beef and tea and had a simple though hearty meal. The Sterno also warmed my cabin nicely.

Shortly after noon the barometer dropped quite rapidly for an hour and a half. Meantime the lake got very glassy. I hunted shelter and sure enough, in three-quarters of an hour we were having as nice a squall as I've seen. It wasn’t a large one but the wind was hard enough to blow spray off the water which is no weather for me to run in. That cleared up soon, however, and I finally docked at St. Ignace for the night.

On Wednesday I was able to get an excellent chart of Lake Michigan at St. Ignace. Now I could travel. Left St. Ignace at eleven and made an easy run to Cape Seul Choix, a little way out of Manistique. There I spoke to the fishing boat Harriet J, owned and piloted by John Goudreau of Naubinway. He invited me on board and Mr. Goudreau, his partner, and I had a regular sailor's dinner. Mr. Goudreau kindly put me up for the night in one of his cottages.

Tuesday the 29th the water was still rough, but the wind had shifted to northwest and the swells were big and deep but long. I rode into Sturgeon Bay without trouble.

The next day I left Sturgeon Bay at 9:10 A.M. The water was still rough and worse yet, the

barometer had dropped from 29.50 to 29.20. The wind had switched to southeast, which 1s the poorest possible quarter for this part of Lake Michigan. Earlier in the trip a day like this would have kept me in, but I was now behind schedule and I had to go on. I arrived at Sheboygan at 1:15 P.M. after a rough trip. The Coast Guard station told me the wind was holding between 25 and 30 m.p.h. Boat and motor stood 1t well but I didn’t like the idea of facing the 55-mile trip to Milwaukee in water like that. So I laid over again.

AUGUST 31st I shoved off for Milwaukee at 7:10 A. M. The wind was just a point off shore but the lake was still very rough. Even so, I docked at the Milwaukee Yacht Club at 10:00 A. M. There a fine reception and luncheon was tendered me by the members and a safe and convenient anchorage for my boat was provided.

The Outboard Motors Corporation factory kindly checked over my engine for me. I knew they would find nothing seriously wrong as the motor seemed to be picking up power and speed all the way along, but I was surprised to find that outside of straightening out a few nicks in the propeller not a single item of any kind needed replacement after 1,800 miles of hard running. That is an eloquent testimonial of the modern outboard. Most large marine engines couldn't show such a record. Bear in mind too, that for almost all of the distance, the motor was turning between 3500 and 4000 R.P.M

What a wonderful six-weeks’ trip that was! It had all of the elements that a good vacation should possess. First, I was doing something that I loved to do. Then I was learning something, seeing new faces, new country, meeting new conditions; the scenery was beautiful, I was active under the most healthful possible surroundings all day long and unlike most vacationers, I lost no sleep but rested long and well each night; I had a definite end in view, a well-formed plan which many vacations lack—in short, instead of tearing down my energy reserves, this vacation trip of mine built them up and put me in shape for about anything that might happen.

to a keen edge. But there isn’t enough exercise to utilize all of the food. I started out eating three meals a day, but after a few days I cut this down to two—namely, breakfast and

dinner at night. I felt better and also escaped the delay which would ordinarily occur if one made a regular scheduled stop for a noon meal. I attempted to carry only emergency rations, very much preferring to go ashore and buy a good breakfast and dinner at some good hotel or, in the smaller towns, at some well-recommended boarding house. A man on a cruise won't take time to cook properly and won't cook the right things. I found that you can always rely on the recommendation of some local person as to the best local boarding house.

I spent only three or four nights in my boat. The rest of the time I slept ashore. I found that I could obtain high grade lodgings in private homes catering to occasional tourists, for from 50 cents to $1.00 a day—in many cases with breakfast thrown in. I was equipped to sleep in the boat, but I like to rest in a good bed and in view of the reasonableness with which accommodations can be secured, I would recommend that anyone choose a lodging house and the extra comfort that goes with it rather than the necessarily close quarters of a small boat like mine.

A night spent ashore leaves you fairly itching to get back on the water again. I choose lodging houses for two reasons—one being that I could get accommodations which were in many cases better than those afforded by hotels, at less than hotel prices, and then again, I did not care to dress up each night in order to register in a hotel and felt uncomfortable about going among other people who are all dressed up and who might look askance at a boatman’s working clothes. Private homes always accept you for what you are and not

what you look like.

Earlier I mentioned that my boat was a step-plane. As the boat was closely examined at almost every stop of the trip, I was surprised to note that every time an experienced boat

man ascertained that I was really using a step boat, his comment would invariably be, “How do you get away with a step-plane? I always thought step-planes were unseaworthy and hard riding in any kind of rough water.” Be that as it may, the bottom of my step boat leaked not at all at the end of 1,800 miles of rough and smooth going. Not a brace, cross member

or knee had been loosened or even as much as cracked. I had been in very rough water several times and not once did the boat's actions lead me to believe that we were even close to capsizing or swamping. I have never seen a conventional Vee bottom outboard boat whose bottom would have stood the pounding as well as my step-bottom. There may be more seaworthy boats than the one that I have, but they will necessarily be slow, and the Pelican design which I followed faithfully, combines speed with safety in exactly the right balance.

Here is another reason why I like the step-plane: Once the boat gets on top of the water in a planing position, you can throttle your motor down to cruising speed and the motor does

not have to labor to run at this speed. This is economical of fuel as well as of the motor itself. With a Vee bottom boat, for instance, the motor has to work much harder all of the

time, for while a Vee bottom boat will plane, considerably more energy is required to keep it planing.

I want to confirm what a good many other salt water sailors have discovered, namely, that the Great Lakes and particularly Lake Michigan, can get just as rough as the Atlantic Ocean

at any time. The swells are not as high as on the ocean, but they are much shorter and break quicker. Blows that kept me off Lake Michigan would not have stopped me on salt water

because of the longer, more even swells. Salt water sailors won't believe this, of course; I didn’t myself until I tried it; but you will find out if you ever try it.

that I bought at various places and shipped home as I went along. I could have travelled much more cheaply than this, but I regarded this as inexpensive enough.

On the trip I used a total of 129 gallons of fuel, two tubes of gear grease, six spark plugs, one Columbia Hot Shot battery and about 15 shear pins. This gave me an average of about 14

miles per gallon of gas for the trip. Such mileage 1s possible only with a step-plane as propeller efficiency is quite high on this type of boat.

Although I carried four or five gallon cans of gas in my boat I did not have all of them filled at one time more than twice on the voyage. I carried just as little gas as I could on a run, for it was my constant effort to keep the boat loaded as lightly as possible and extra unneeded gas only slackens your speed that much.

So that was my vacation for this year. It was the best one I have had thus far. The best proof that it was highly worthwhile to me lies in the fact that I have already planned a similar trip for next year. Why don’t you plan one, too?