The following day we got an early start because we knew we faced the ordeal of getting over the unworkable lock at Lockport.

The following day we got an early start because we knew we faced the ordeal of getting over the unworkable lock at Lockport. The run of five miles from Joliet to Lockport was made in an hour despite the swift opposing current. Still in waters polluted to the Nth degree we faced one of the most difficult labor jobs of the entire transcontinental cruise.

Below:

VIEW OF EXTERIOR LOCK WALL, POWERHOUSE, DAM, AND CANAL FROM OLD LOCK.

LOOKING NORTHWEST. - Illinois Waterway, Lockport Lock, Dam and Power House

LOOKING NORTHWEST. - Illinois Waterway, Lockport Lock, Dam and Power House

|

| Powerhouse |

|

| Powerhouse |

|

| I think this might be the track going through the power house Hoag speaks of in the paragraph above. The photo is from the Library of Congress. |

After all the filth we had come through in the Illinois River and the Illinois and Michigan canal, we had contemplated the Chicago Drainage Canal with horror. But, strange as it may seem we did not find it by one one hundredth part as bad as the polluted waters we had previously traveled. The odor of sewage is almost imperceptible. The water appears to be quite clean, and there is scarcely any indication of the indescribable pollution we'd experienced further down the state. The reason for this condition was quite apparent. In the drainage canal the sewage has no chance to become stagnant. The canal is 226 feet wide, 23 feet deep, and flowing at the rate of three to four miles per hour. The sewage is thus so diluted with an abundant flow of pure Lake Michigan water that the pollution is virtually lost. It is down state further when the current decreases, where the sewage becomes stale and stagnant that the real pollution begins. However, we were pleasantly surprised to have our preconceived ideas of the Drainage Canal changed.

Although it was nearly four o'clock in the afternoon before we got under way from Lockport, and the heavy current in the canal retarded our speed, we entered the outskirts of the Chicago industrial district about sundown. We were anxious to get into the city, so once more we violated all our solemn vows against night traveling. When darkness closed down around us, we lighted our running lights and pushed on. Presently we were scooting under bridges too numerous to mention, dodging tugs and barges, and sliding past great industrial plants, grain elevators, and all the assembly of dingy structures, smells, dirt, grime and noise that it takes to make the least attractive section of the nation's second largest city.

Below: 12th Street Bascule Bridge, Chicago, Illinois, circa 1900.

This picture was complete, even to an occasional cinder or pinch of dirt in our eyes long before we passed out of the Drainage Canal into the Chicago River. Our night run through the Chicago River from the point we entered it beside the Bridewell City Prison was another nightmare of nocturnal navigation. For six miles we forged ahead against the current with millions of lights dazzling our eyes, both motors roaring - shooting blue fire out the exhaust ports, and the river itself as dark as a cave in the banks of the Styx. The river was full of every manner of driftwood and debris, and with bridges every few hundred yards where only Stygian blackness between the red lights of the bridge piers indicated the open water spaces for which we should steer.

|

| This is the Western Avenue swing bridge they went under. The canal was drained temporarily for construction. For more fantastic pictures go to this Chicago Tribune site! |

All the Chicago bridges were high enough to let the Transcontinental under, although many a time we bore down upon some dimly silhouetted mass of steel without being real sure whether we were going under or not. Under every bridge, street cars, taxi-cabs, and a hub-bub and jam of motor traffic, shook clouds of dirt down upon us, to keep us wheezing and rubbing our eyes.

All the Chicago bridges were high enough to let the Transcontinental under, although many a time we bore down upon some dimly silhouetted mass of steel without being real sure whether we were going under or not. Under every bridge, street cars, taxi-cabs, and a hub-bub and jam of motor traffic, shook clouds of dirt down upon us, to keep us wheezing and rubbing our eyes. It was with somewhat of a feeling of relief that we went under the Wabash Avenue bridge, and came in sight of the handsome structure that spans the river at Michigan Avenue in the full glare of the floodlights illuminating the Wrigley Building and the massive tower of the Chicago Tribune.

The municipal landing at Michigan Avenue beside the Wrigley Building was where we had planned to tie up. The spot was as light as day. We were delighted to find a group of newspaper reporter friends, and plain curiosity seekers, there to meet us. Among the crowd there was also a representative from the Evinrude Motor Company of Milwaukee, whom the factory had dispatched to Chicago to see that anything the factory might do for us was doe. The flashlights boomed, and by the time we got through with the handshaking and the interviewing, it was midnight before we got to a hotel. I got a bath, got to bed and asleep, only to be routed out by the jangling of the telephone, and the operator saying - "Milwaukee is calling you." It was H. Biersach, General Manager of Evinrude Company on the wire _ wanting to know what he might do to help us along, and requesting me to hurry along to Milwaukee. He was holding up a meeting of the company's board of directors until I could get in to give them every possible suggestion as to how a better outboard motor might be built.

|

| Chicago Harbor Light |

So, at nine o'clock in the morning instead of remaining in bed where we'd have preferred being, we were off through the Chicago River heading for the lighthouse at the end of the breakwater and the broad expanse of Lake Michigan beyond.

Our introduction to Lake Michigan was anything but cordial and friendly. We rounded the end of the breakwater to go slithering up the side of a green mountain of water, and over the top just as the peak curled into a rooster's tail of white spray. Most of the spray came down on top of us. We made a sickening descent down the other side of the wave. Then the boat buried her nose in a trough at the bottom, and we took a geyser of water over the forward deck as it washed back, struck the combing around the cockpit, and shot skyward. The first wave, of course, was followed by another one just like it, and then another, and another, and another.

By this time we'd gone into slicker coats and sou'westers, and were heading up the lake with the weather pounding us on an angle of about thirty-five degrees on our starboard bow. We were shipping far more water than was good for us from the standpoint of safety. Every time we went down a wave the bow of the boat seemed to head pretty well for Davy Jones' Locker before it would rise again. After having tried the craft out in some very heavy weather in the Pacific Ocean off Los Angeles Harbor it was apparent to me that we were at least six hundred pounds over loaded. This deduction was made giving due consideration to the fact that most of my boating experience has been in salt water where the waves do not develop the short, choppy, quickness, that characterizes the surface undulations of these inland fresh water seas.

When it became necessary to throttle the motors to keep the boat from swamping, I decided the most discreet thing to do was to go ashore and unload about a quarter of a ton of excess baggage before we put the whole outfit in the bottom of the lake. The most convenient place to do this was the Chicago Yacht Club's basin in the Lincoln Park Lagoon. We therefore changed our course, and wallowed along in three miles of seething water until we reached the quiet water beyond the opening of the lagoon. Meanwhile the wind seemed to have been increasing in violence. Water had been lapping over our stern before we got into the yacht basin. But when we got there I went out on the beach, and took a look at Lake Michigan it seemed incredible that our overloaded cockleshell could have lived for a single minute in such a sea.

After pulling out about 800 pounds of miscellaneous gear that we felt could be dispensed with to better advantage on shore than in the lake, we took the boat out again for a trial run, and to observe results. By this time the lake was much rougher than when we came in, but we found out the boat rode like a different craft. Instead of wallowing down into the waves like a pig going under a fence, she rose on top of them like a cork. But, she pounded so badly and the lake was was running such a furious sea that it seemed utterly foolish for us to attempt traveling until more favorable weather. Accordingly, we spent the rest of the day getting our surplus equipment boxed and shipped. Accordingly, we spent the rest of the day getting our surplus equipment boxed and shipped. Getting turned back by the weather, however, was not entirely without its compensations. That evening I got a home cooked dinner, and a real night's rest at the home of friends in Chicago - something I had contemplated during the forenoon as an impossibility only to be wished for.

Next morning we found the lake still rough enough to satisfy anybody who might have been looking for a thrill in a small boat, but not nearly so angry as it had been the previous afternoon. If it got no worse, there was every indication that we'd be able to knock a fair portion of the run from Chicago to Milwaukee. So, we shoved off getting under way at 8:30. We took a lunch aboard, and for the rest of the day watched the shores of Illinois and Wisconsin slip along past our port side. After we'd been under way for about two hours, the lake began to calm down to a gentle rolling sea free from white caps. Naturally this helped our speed.

We lunched in the boat as Waukegan slid past about three miles abeam of us. As the lake continued to become more placid during the afternoon we increased our distance from the shore. This took us safely outside the several bad reefs that are charted along this portion of the Illinois and Wisconsin shores, and also reduced the distances which were materially increased if we were compelled to follow the long sweeping curves of the shore line. At four o'clock in the afternoon Kenosha, Wisconsin, was visible in the dim distance abeam of us. Then, we changed our course, and began heading for Racine. At five thirty we put-putted into the harbor, tied up for the night, and flagged a taxi to take us to a hotel.

A telephone call to Milwaukee put us in touch with the officials of the Evinrude Company to inform them we'd be in the Milwaukee River at noon the following day. It also resulted in a pleasant little surprise for us. Leaving Racine at nine o'clock next morning we found the lake fairly calm. We rounded wind point, the long point above Racine keeping about three miles out at sea. But that time we could see the smoke and dim outline of Milwaukee in the distance.

|

| Wind Point Lighthouse - Source: U.S. Coast Guard |

|

| State St. Bridge on Milwaukee River |

When the tug came nearer we could see that her forward deck was festooned with men, and in the bow waving like a human semaphore the field glasses picked out the countenance and spectacles of Fred O'Neil, Vice President of the Evinrude Motor Company, Ed Wehe, Manager of the Service Department, and a few other familiar faces. After coming alongside of us and exchanging greetings, the tug led the way into the Milwaukee River with Transcontinental trailing her astern like a Mother Carey's Chicken following a ship.

Somebody around the Evinrude establishment had done a good job of press agenting. The newspapers had been kept full of the story of the Transcontinental for several days. That morning the papers carried pictures of the boat, and a news story to the effect that the craft was due to arrive in the Milwaukee River at noon. Moreover, it was Saturday. Hence, when we came up the river trailing the tug, and the tug captain blowing an extra head of steam out of his boilers through the whistle, most of Milwaukee, it seemed, hurried to the waterfront. The banks of the river were jammed with people. There was a grand rush for standing room on the approaches of the various bridges - all of which had to be opened to let the tug pass. Every window in every building facing the Milwaukee River became a frame for a living picture of humanity peering out to get a look at the first boat attempting to cross North America, and now more than 3,500 miles on its way.

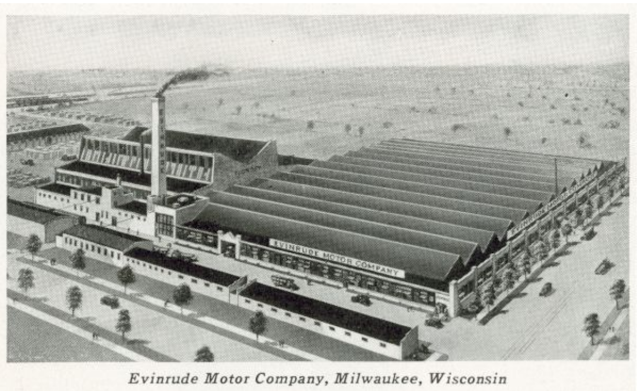

After doing our little grand stand stunt in the Milwaukee River, we proceeded to the Milwaukee Yacht Club, where the club was virtually turned over to us, and we were met by the usual crowd of newspapermen and a delegation from the Evinrude Motor Company. The yacht club on a Saturday afternoon would have been a lovely place to loaf around - doing nothing. But there was important work to be done. We lunched at the club, and by that time a truck was waiting outside to move Transcontinental, and our entire outfit to the Evinrude plant. While the boat and motors seemed to be in excellent shape, we still had 2,000 miles to go. The motors have been run from Astoria, Oregon, to Milwaukee. They had run at full throttle from 8 to 10 hours per day - day after day, and week after week - without ever having been pulled down for an overhauling, and without the replacement of a single part except the underwater mechanism which had been consumed by the silt in the Missouri River. The Evinrude engineers desired to measure the pistons, cylinders, and other parts for wear. And, from our standpoint, with the Evinrude plant and boatworks available for any necessary repairs or alterations we'd have overlooked a rare opportunity had we gone out of Milwaukee without having everything right.

|

| 1929 |

Although we had a full 18 inches of freeboard astern - ample for the roughest river work we'd encountered, we found it was none too generous for the infamously choppy seas of the Great Lakes. Some sort of spray hood over the bow of the cockpit was also desirable. The boat had not leaked a drop since first put in the water, but she had begun to look as if a coat of paint wouldn't do her any harm.

So, we hauled the boat out to the Evinrude plant where the most skilled mechanics and carpenters who could be mustered into service for a Saturday afternoon and Sunday job were put to work. Never have I seen any group of men who worked so carefully. Every man of them seemed to feel that the success of their company's product in driving the first boat across America depended entirely upon him. While the carpenters were sawing out boards to make an 8-inch spray combing around the stern, and the after six feet of the cockpit; the mechanics in the service department dissected LEWIS and CLARK. Meanwhile an awning maker was stitching a heavy canvas together to form a curved hood over the forward end of the cockpit to keep the Great Lakes from climbing aboard.

The motors, however, gave us the biggest surprise. In spite of the terrific punishment they had received, a systematic "micrometering" of parts yielded no appreciable wear. There was not a single part to be replaced - nothing to be done but put them together again and touch them up with a new coat of paint. In selecting a stock of spare parts for the remainder of the cruise we also profited from past experience. We had no more Missouri Rivers to cruise, hence there was no necessity whatever for taking along a stock of stuff that probably would never be used for anything but ballast to be chucked overboard in case of squally weather. So, the stock of parts we took along was no more than could have been carried in one's hat. Of course, we had two motors, and never intended to use but one until we reached the Trent Waterways in Ontario. This gave us a whole motor in reserve, and to rob parts from it if necessary.

By Tuesday morning the paint on the hull of the Transcontinental was sufficiently dry to permit launching other boat again, so we trucked her to the Milwaukee Yacht Club, and into the water. A trial run into the lake, out beyond the Milwaukee Light Ship, in a sea that was far from calm revealed that we were much better fitted for deep water cruising than we had been when we entered Milwaukee. During our stay in the city that malt beverage made famous prior to Mr. Volstead's essay on enforced temperance, we got acquainted with Captain William Kincaide, commander of the United States Coast Guard Station at Milwaukee.

|

| The Milwaukee light ship. She was in service until 1932. |

The thing appeared so to me, and I would have been cold-footed on the subject from the start but from having observed the tremendous number of ships that ply up and down the entire length of Lake Michigan. It seemed to me impossible to cross the the lake and be out of sight of a ship at any time. Moreover, most of the ships are slow freighters, with very little, if any more speed than we had. With fair weather, it seemed reasonable that we would be able to get across the lake in a daylight day and without the slightest difficulty. Of course, if we got caught in a squall out in the middle of the lake, our predicament would be anything but safe or comfortable. But, if we did get caught by unfavorable weather, it seemed certain that we could count on being close enough to a ship to permit going alongside and yelling for help.

So, after much careful thought we decided to attempt the dash across the lake at daylight the following morning - providing weather indications were favorable. We got everything ready, and then spent most of the night around the coast guard station grabbing every weather report and watching the barometer. When the first rays of daylight began to show in the east every weather indication appeared to be in our favor. We were about ready to shove off when Captain Kincaide came down, and stood on the shore watching our preparations. He stood there stroking his chin as if in deep thought. Finally, he spoke saying: "Boys, if your'e going to try it, I'm going to go with you." He handed me a telegram - an authorization from the Commandant of the Coast Guard Service at Washington for the Captain and a crew of men in a motor life boat to accompany us safely across to the Michigan side of the lake. I thanked the Captain for his his spirit of kindly cooperation. To this he replied: "Well, me and the boys would like to take a little trip anyway. There hasn't been much doing on the lake this summer. Besides, I'd rather go WITH you, than to come out AFTER you. Shove off whenever you are ready, and we'll catch you with the life boat a few miles beyond the light ship.

This sudden and wholly unexpected co-operation on the part of the Coast Guard was thoroughly appreciated, for it took out the element of uncertainty, and about 99 per cent of the risk out of us getting across Lake Michigan. We shoved off from Milwaukee feeling much less uneasy as to what we might encounter on the run of 98 miles of open water between there and Ludington. In a few minutes we were outside the breakwater with Transcontinental burying her nose in the choppy sea of a morning breeze. Half an hour later we cruised pass the lonely Milwaukee Light Ship took our course from the compass, and headed straight out across the lake. The shores of Wisconsin were getting somewhat hazy and dim in the distance when a tiny white speck coming up astern of us loomed in the field glasses as Captain Kincaide's life boat. The life boat had scarcely half a knot more speed than we did. Consequently, the scenery consisted of sky and water before the convoy caught up with us.

By rare good luck, the favorable weather that had been forecast turned out to be even better than we'd hoped for. By the time we'd been out of Milwaukee two hours the wind died down completely. It became unbearably hot, not a breath of air stirring, the lake flattened out like a bowl of soup. It was one of those rare days to be expected about once in an average human life time on Lake Michigan. Luck was certainly with us. We cruised much of the time within twenty feet of the convoy, often talking with Captain Kincaide and his men through a megaphone, or using the megaphone as an ear trumpet to pick up voices from the other boat over the roar of our engine.

At noon we took our position, found we were approximately in the middle of the lake, and with a mill pond surface as the prospect for the rest of the day. The barometer remained absolutely stationary. The torrid weather we were experiencing out on the lake gave us sympathy for the heat sufferers in Milwaukee and Chicago that day.

About one o'clock in the afternoon a chipping sparrow came fluttering down out of the sky, landed on the bow of the Transcontinental. After roosting there for a while, apparently recovering his breath, he hopped off and went aboard Captain Kincaide's boat. The appearance of this small land bird called attention to the fact the Great Lakes are a death trap for billions of of land birds and insects every year.

Numerous flies, flying beetles, and butterflies were observed in the air and on the water. They came aboard in such numbers as to become an intolerable nuisance. We put on several active fly drives, swatted flies right and left, and shooed them overboard, but only to pick up a new cargo of the pests within the next fifteen or twenty minutes. We saw butterflies, and other insects go fluttering down into the water, apparently so exhausted they could remain in the air no longer. It is very evident that these flying creatures get carried by the air currents out into the Great Lakes, dropping to their doom when they can remain a-wing no longer.

While we were usually trailing our convoy, we really had no more need for it than the average man would have for a hundred hats. The weather remained the same across the lake, and there was never a minute during the entire day that we were not in sight of from one to a dozen different ships. Al this, of course, while the fine weather lasted. We were just as well satisfied to have the convoy with us.

About the time the sun dropped big and red into the world of water around us we began to smell land. A peculiar haze also appeared in the east, indicating the presence of land. But, darkness settled down around us, and still no land was in sight. About nine o'clock in the evening a little light bobbed up on the eastern horizon, and began to blink at us. I glanced at the chart, and thought I identified the light as Little Sable Point - just south of Ludington.

Cruising on for another half hour three more lights appeared in the east, but to save our lives we couldn't make the various lights jibe with the charts. Presently a great cluster of lights came into view indicating a town - evidently Ludington. During the entire day we left most of our navigation problems to Captain Kincaide because we reckoned with his large binnacle and steadier boat, his reckoning was apt to be more accurate than ours. About the time the lights of the town came into view Captain Kincaide's boat suffered a breakdown. We went alongside asking if he needed a tow, but he assured us he'd be under way in just a few minutes, and suggested we cruise on. So, we went on towards the town, but still deeply puzzled over our inability to identify the various lighthouses on the shore and check them with our chart.

At midnight we pulled in between a couple of breakwaters. Our harbor chart of Ludington was broken out, but the whole scheme of lights and landscape ashore seemed to be askew with our charts. Several years ago I had been in Ludington, and I still had something of a mental picture of the town and its harbor. But, this place, into which we poked the bow of Transcontinental after sixteen hours of steady traveling, was nothing that I'd ever set eyes upon.

We pulled in between the breakwaters, and when I espied a man on sore, I shut down the motor, and called out: "What port is this-please?" "Manistee," came back the reply. "Manistee. Holy cats," I exclaimed. "NO wonder we have been sixteen hours getting here."

We'd cruised 120 miles that day instead of the 98 miles we expected to cover from Milwaukee to Ludington, and we were about 25 miles nearer to New York than we expected to be.

Presently, Captain Kincaide joined us, and I ventured to ask him if he knew what port we were in. "Sure I do," was his answer. "This is Manistee. I've been heading for it all day. When I saw the kind of weather we had on the lake today, I knew you wouldn't object to getting lured along a little farther on your route." With that the Captain burst into an uproar of laughter, and we joined by the crews of both boats. The biggest part of the joke on us was that our compass had been off about half a point all day. We'd been heading for Manistee when we thought we were headed for Ludington. We were only 25 miles off on a course of 120 miles - just a mere detail for a trio of landlubbers trying to navigate the Great Lakes in an 18-foot put-put.

While we were delighted to be in Manistee that evening in preference to Ludington, the unintentional alteration of our route cost me about ten dollars for telegrams. When we left Milwaukee, the Milwaukee newspapers carried the report that we had struck out for Ludington. When we failed to show up at Ludington, a couple of reporters who'd been mastheaded on the breakwater all evening, drew the logical conclusion that we were LOST. Forthwith, the report went out on the wires that we - "were lost in Lake Michigan without food or water." It would certainly be a terrible thing to be lost on Lake Michigan without any drinking water - especially on a hot day. Nevertheless, I had to get out a handful of telegrams to our relatives and friends to let them know the report was grossly exaggerated. I learned later that Mrs. Hoag read the report in the Los Angeles paper, laughed over it, and ten minutes later received my wire announcing our arrival in Manistee.

It was a good thing for us we got across Lake Michigan on the day we did rather than to have attempted it the following day. We got a short night's rest in Manistee, and were on the job for a dash up the lake next morning - but we didn't go anywhere the next day. We came out of the hotel to find a violent gale blowing from the northwest. Captain Kincaide, with his non-capsizable, non-sinkable life boat was preparing to shove off for Milwaukee. He advised us to remain in port, but time was getting to be such a precious element with us that we

|

| 1960 breakwater at Manistee |

Lake Michigan was literally boiling. Never in all my travels have I seen such a mess of green mountains and white froth as we encountered that day. The first wave that struck us all but capsized us bow over stern, and for an instant I couldn't see the sky for the water going over the top of us. When we climbed the green wall of water and topped the summit we went hull out of the lake completely - dropping with a sickening thud into the foaming aquatic chasm below. Every time we went up the muffler of the motor went under with a loud hiss and gurgle. Then we'd go careening skyward again, take to the air, and drop like a thousand bricks. Meanwhile we could scarcely see for the spray, and our gimbel-mounted compass was doing flip-flops like a foundry tumbler. Water was coming aboard about as fast as our double-action bilge pump could put it overboard. Although Transcontinental was a mighty staunch and seaworthy little hull, it was obvious to me that no boat ever built could stand that sort of punishment very long. It was obvious too, that we could take the punishment of pounding around all day in that sort of sea, battling to stay afloat, and have nothing but bruises and strained nerves to show for it at the end of the day.

In an hour of ceaseless hammering, we'd made just about two miles up the Michigan shore from the Manistee breakwater. At this juncture we came to the agreement that live cowards get more out of life than dead heroes - and there's a vast difference between and adventurer and a fool. We decided to put about, and run for Manistee. Just how we ever got turned around in that sea without swamping is something I'll never be able to explain, but somehow we did it, although while we were making the turn water was coming aboard by the bucketful. In another instant we went yawing off down the tail race of a green mountain of water. Then we stood still - wallowing between waves slowly climbing to the next foaming summit, taking the spray, and yawing off again. We managed to get back to the opening between the breakwaters in a series of yaws, wallows and dousings.

When we reached the Coast Guard Station we found Captain Kincaide still there.

"Decided to take my advice - eh?"

"Aye, Captain" we responded.

"Well, you show good judgement."

(To be continued)

No comments:

Post a Comment