This is Part 4 of the serialized story. It turns out the publisher put photos out of order in the articles. Part 3 and this part had photos belonging, logically, in a previous part of the cruise. I'll put them in here, and also go back and place then where they belong for future readers!

Don't forget to join AOMCI if you are interested in the early outboards as we have many people who can help you get started exploring this exciting period of outboard technology.

|

| Entrance to Manistee Harbor around 1910 |

|

| Current satellite view of Manistee |

Next morning the wind had abated somewhat. It was still blowing from the northwest, and the lake was running wild from the lashing received the day before. When we rounded the breakwater, we decided to attempt the run of twenty-eight miles to Frankfort, in spite of the fact that the surface was but little smoother than the sea that chased us back to Manistee in our previous attempt to make the same route.

Between Manistee and Frankfort there were two harbors we might run into in a pinch - Onekama, ten miles north of Manistee, and Pierport, four miles above Onekama.

North of Pierport there was no possible chance of a landing, except to beach the boat, until we would reach the sheltered harbor of Frankfort. Arcadia, ten miles south of Frankfort, showed on our charts as a sheltered basin with a 3 foot channel leading into it. A three foot channel gave promise of being dry in spots between the furious waves that were pounding against the shores of Michigan from the other side of the lake.

|

| Pierport's story is interesting. |

My reference to the lowering of the lake levels prompts me to venture a few comments on the subject at this point of the story. The lake levels have gone down alright, and in seeking to account for it the majority of people have looked o further than to see just one obvious cause the Chicago Drainage Canal. We heard the hue and cry from Racine to Sorel, Quebec, and the arguments against the drainage canal seem to be so firmly entrenched in the public mind that one might as logically argue the failure of the Volstead Law with hidebound prohibitionist. Far be it from me to praise Chicago's action. I've already done precisely the opposite in previous paragraphs. But looking at the situation with an open mind, and with the background of experience having traveled oner the whole water area affected, I believe the Chicago Drainage Canal is only part of the answer. Certainly the water flowing out through the canal isn't a drop in the bucket compared to the Great lakes. I don't think the canal could ever take four feet of water off the lakes any more than I could syphon out Los Angeles Harbor with a piece of garden hose.

We do know the last few years in the Great Lakes watershed have been years of scanty rainfall.We know that the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers have been deepened for navigation; and that rocks, rapids and other obstructions in the St. Lawrence River have been blasted and dredged out. In heaping the blame upon Chicago, every factor that might be a cause or a contributing cause seems to have been overlooked, except the visible one that affords such a convenient scapegoat. With this handy target for the brickbat of blame to be heaved at, folks seem to have forgotten that natural watersheds have a lot to do with the maintenance of water levels in lakes. Thus, they have also overlooked the fact that a vast area of the timberland - the natural watershed of the Great Lakes has been ruthlessly destroyed. That has undoubtedly curtailed the amount of water now flowing into the lakes.

Stopping the flow of the Drainage Canal certainly would not alter that condition, and I doubt if such an action would restore the lake levels by a single inch in the next ten years. Until some group of engineers and corps of hydrographers have been assigned to the task of making a study of the subject over a period of years we will remain without authentic data as to just what is becoming of the Great Lakes.

Meanwhile, Chicago will probably remain the scapegoat, even though it seems the loss of lake water through the Drainage Canal should have been offset by the Volstead Law which curtailed Milwaukee from mixing the water with malt and hops and retailing it in bottles and barrels.

|

| Hmph... this should have been with Part 3. Shame on the publisher. |

The contortions that Transcontinental went through that morning were utterly indescribable. Wilton and Woodbury took turns at the wheel while I remained aft to see that our motor power didn't let us down.

The contortions that Transcontinental went through that morning were utterly indescribable. Wilton and Woodbury took turns at the wheel while I remained aft to see that our motor power didn't let us down. Time without number I couldn't see the sky for the water going over us, and when I found difficulty in trying to keep myself in the boat, I strapped myself to the seat with a couple trunk straps. Meanwhile, Poor little Spy was as about as miserable a picture as was ever created in dogdom.

No doubt he thought his human companions had gone completely insane, and that the boat he was in outclassed the widest bucking horse that ever kicked the dust of a rodeo. Whenever he attempted to move about it was only to get thrown down, or slammed violently against some part of the interior part of the boat. The deck was continually going off and leaving him in the air and occasionally he got bumped so hard that he howled. If his canine psychology could have been interpreted, I'm sure he'd have reached the conclusion that all the fire departments of a dozen big cities were having fire hose practice with Transcontinental as their target. Finally he sought refuge under the forward seat and between his master's ankles, and never even came up for air until we reached the quiet waters of Frankfort Harbor. If any tender hearted person might accuse us of cruelty to an animal by reason of having the dog along, I might add the three human animals got no more enjoyment out of it than did the dog.

We pulled into Frankfort at noon, cold, hungry and drenched to the skin. A local coal dealer lent us a shed, where we took turns skinning each other out of our wet garments. Dry clothes from the forepeak, and we adjourned to a restaurant where we all but wore out a waitress with the demand for hot soup. Lake Michigan, to use a popular slang expression, just about had our goats. I felt like Edgar Allen Poe when he quoted the raven "nevermore" - under such conditions. I didn't care if the transcontinental cruise ended right there. All the glory of being the first man across North America with a motor boat wasn't going to amount to much if I had to die a hundred ordinary deaths to get there.

With a full stomach and dry clothes, I left Wilton and Woodbury strolling on the docks, and walked out on the breakwater to have a look at the lake. Of all the seething cauldrons of fury I have ever looked at, Lake Michigan that day would have taken all the prizes. I sat down on a portion of the breakwater where the waves couldn't quite get over, and could scarcely believe my eyes that our little boat had actually lived to drive through 28 miles of such seas.

The more I watched, and thought about it, the more I became convinced that if a man is born to be hanged - he isn't liable to drown. Then, sitting there, I began to meditate over what queer ideas some men have of pleasure. I could think of no more comfortable place at that moment, and no place I'd rather be than in the living room of my own home in California. Had I chosen to do so, I might have been sitting before a wood fire in an open fireplace at home - reading, smoking my pipe, or just loafing around petting my wife as I'm usually doing when blessed with sufficient intelligence to stay home. But, there I was out trying to cross North America in a motor boat, a feat that had never been dome, and which the majority of sane people regarded as impossible. I was half successful, and yet, half defeated; and knowing full well that I'd be condemned if I failed, branded for a fool if I drowned, and with scant praise of financial return if I succeeded.

After half an hour's effort I gave up all attempts to analyze that trait of a man's make up known as love of adventure: "All for prominence, so I am told,

And a few pieces of yellow filth called gold -"Taking another look at the lake, the wind had died down to a gentle zephyr, and the waves were no longer crashing over the breakwater. I sauntered back to Frankfort, and told Wilton and Woodbury I was ready to shove off again if they felt like taking more punishment. Twenty minutes later we were heading around the breakwater, heading for Betsie Point. The sea was still choppy, but nothing like the infuriated jumble of water through which we had pounded all morning.

|

| Point Betsie U.S.C.G. Station |

|

| Glen Haven is now an historical village part of Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. An old USCG Life Saving site there, too. |

By this time South Manitou Island had begun to loom into view twenty five miles away. Sleeping Bear Point, around which we were heading for the Port of Glen Haven somewhere over the northern horizon.

The lake had quieted down so that we were taking no chances in running a course eight miles off shore across Betsie Bay. Although

CLARK, the motor we were using, was kicking the lake astern of us at a very good clip, we didn't seem to be getting anywhere.

CLARK, the motor we were using, was kicking the lake astern of us at a very good clip, we didn't seem to be getting anywhere. But, eventually the Sleeping Bear began to show signs of life by crawling up off the horizon. This portion of the shore of Michigan is nothing but a wall of sand dunes - dunes that rise in a beautiful sweeping curves from the water's edge, and topped with coniferous trees that struggle for life between the shifting sands and sweeping winds.

In some places, however the dunes rise almost perpendicularly from the shore of the lake, and with the charts showing deep water right up to the sand walls.

By the time we crawled around the end of the Sleeping Bear's nose, all of Lake Michigan's pent-up fury seemed tp have been spent. The surface flattened out like a pane of glass. There certainly wasn't a trace of ursine carniverousness such as we would have most assuredly have encountered had we attempted to round Sleeping Bear Point during the gale of the morning or the previous day. Lights were beginning to blink on South Manitou Island, and from several points along the mainland shore when we altered our course to the south and east toward the village of Glen Haven at the lower end of Sleeping Bear Bay.

Pulling up to the pier at Glen Haven we found it a very good place to tie up in calm weather, but no place at all if the lake got the least bit rough. We tied up temporarily under the pier, and went to a hotel on shore. After dinner it was decided that Wilton and I would remain at the hotel, while Mr. Woodbury anchored out to sleep aboard the boat.

Early next morning we found a strong off-shore wind blowing. Wilton and I breakfasted, and then went to the dock where we had to splash stones in the water around Transcontinental before we succeeded in breaking out the Watchman aboard the boat. Somebody had to stay aboard, so the cameraman and I went aboard, while Val went ashore for his breakfast. That morning we learned another lesson about Great Lakes weather, and that was that lee shore breezes are just about as bad as open water winds on these notoriously choppy inland fresh water seas. Shoving off across Sleeping Bear Bay in the direction of Good Harbor Point it was necessary for us to go about four miles off shore for a run of six miles. Two miles off shore the lake was just about as rough as if the same breeze had been coming straight across from Wisconsin.

Rounding Good Harbor Point we faced a run of twelve miles of open water eight miles off shore, taking the sea half astern and half on our starboard beam. That run was anything but a picnic, or a tonic for unsteady nerves. The sea became almost as rough as we had it in the morning before, except the waves were shorter and choppier. They seemed to be about twelve feet high, and about six feet apart, coming from nowhere in particular, but all fighting each other, and trying to get aboard.

The sea was just enough astern of us to send us continually yawing off our course, and to keep Mr. Woodbury playing an imitation game of roulette at the steering wheel. We yawed all the way across Good Harbor Bay, and began running for Cat Head Point on a twenty-mile course, that took us about ten miles off shore. Long before we got there we came to the conclusion that there was a bit more sea running than we had any business being out in. We were playing hooky from Davey Jones' Locker if we attempted to go on, but there didn't seem to be anything indicated on the chart that looked like a place where we could run for cover. The village of Leland with a miserable shallow little harbor formed by two wooden breakwaters running out from the estuary of a tiny river, appeared to be our only chance. We were equipped with a large sea anchor that was fitted with a most ingenious device for spraying oil upon the troubled waters. With this anchor we knew we could heave to and ride out almost any storm that ever blew, but the shifting of the wind to an inshore breeze vanquished that as a feasible possibility. If we hove to it would be only a matter of time before we'd be on the beach, and in worse trouble than in the open water.

|

| Leland Harbor |

All this time we were traveling like a surf board over the waves, When we got within a quarter mile of the shore it was obvious that we were traveling at something like automobile speed. Of course we almost stood still when we wallowed down between the waves, but as we yawed off down the next slope we'd speed ahead until the motor simply could't hold the pace. As we slid down the long green slopes the engine would race until it sounded like an electric fan. In almost less time than it takes to tell it we covered the last quarter of a mile toward the shore. I took a look at the tiny opening between the two breakwaters with the sea pounding straight into it, waves going completely over the breakwaters, and realized we were going to be lucky if we could hit the hole without crashing. I backed off on the motor throttle, but when I saw it apparently decreased our steering control, I reasoned our chances were for hitting the opening were best if the motor was given full speed ahead. With that I gave CLARK all he had, and shouted to Wilton who was at the wheel to steer for as near the middle of the opening as he could possibly go. The white sand bottom of the lake was flying under us, the tops of the ground swells were tumbling aboard as we bore down upon the narrow channel - seeming at express train speed.

We yawed sideways down a huge swell. Wilton put the wheel hard over to the right, but the boat refused to change course. We did the last hundred yards, it seemed, in nothing flat, and were heading almost broadside for the end of the breakwater to the right of the opening. "Hold her over, Frank - we're not going to make it," I called out to Wilton. But, the cameraman was holding her over. He had the wheel over as far as it would go before the boat began to respond, and we shot around the end of the breakwater in a cloud of white spray - missing the end of the rock ballasted piling by no more than six feet. We touched bottom twice as we shot around in a sweeping circle within ten yards of the beach. Our bow climbed back through the boiling surf, and in another minute we were heading for the open lake.

|

| Way cool! It DOES look like a cat head! |

When we were out in the open water once more the motor was still shooting on both barrels as if it never know how to do anything else. The lake was still getting rougher, and we were being unmercifully pounded, but anything seemed preferable to a second tampering with the jack pot from which we'd just emerged.

We cruised on out into the lake trying to decide whether we should attempt to run around Cat Head Point into Northport Bay, beach the boat, or make another try for Leland. Our chances for getting around Cat Head Point without swamping were decidedly precarious. If we attempted to beach through the surf that was running, we'd probably damage the boat to be laid up indefinitely for repairs. On the other hand, getting in between the breakwaters without hitting anything was a possibility. We decided to try again.

|

| Below: Leland Harbor fishing boats |

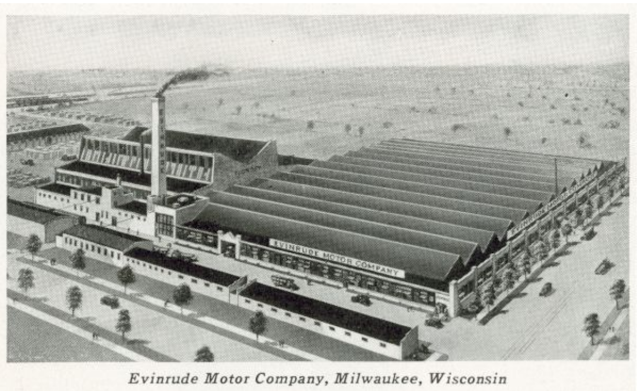

Although we got into an awful snarl of water where the current from the stream came in contact with the waves, we got through it, scraped bottom two or three times, and began bucking the current to the foot of the hydro-electric plant tail race at the head of the tiny bay. In another minute we were tied up at the landing barge, with most of the town of Leland waiting to give us a glad hand. Never in my life have I had more respect for any inanimate object than I had for the Evinrude motor of our's at that moment. That motor had kept going when by all the laws of nature it should have quit. And, but for the fact it DID keep going, and the high efficiency of the propeller method of steering, we certainly would not have been on shore with ourselves, boat, and outfit, all intact.

|

|

| Current harbor configuration |

Having anticipated rough going that day we certainly weren't disappointed. The wind had shifted around to an off shore breeze again, but as we had to stay out several miles in the lake to keep clear of dangerous reefs, we got all the benefit of the weather quite as if the waves might have been rolling down from the North Peninsula of Michigan. Our cruise from Leland to off Cat Head Point was a three hour wallow and dousing with the motor running at about half throttle, and the weather squarely upon our starboard beam. Cat Head Point seemed appropriately named, for when we got there the water in the vicinity was showing feline fury - teeth, claws, hissing hatred, fluffed up fur, and swishing tail; in fact everything that Lake Michigan can do to make its ferocity comparable to that of irate cats, from tom cats and pussy cats to African leopards and Bengal tigers.

Next came Cat Head Bay, another cat-like, treacherous, reef-strewn bight of water, through which we ran for five miles, and about the same distance off shore into Grand Traverse Bay. Grand Traverse Bay is usually one of two things. It is a vast pond of mirror-like placidness, or a heaving tumbling mass of trouble for small boats. Some years ago I spent part of a summer on Grand Traverse Bay, and had learned that no familiarities were to be taken with it. Thus, when we rounded the corner of Leland County about two o'clock in the afternoon, and found Grand Traverse Bay in anything but a peaceful mood, I had little stomach for attempting to cross that day. We were then riding more sea than we had any business being out in, and with every indication that it would be much worse before we could reach the shores that were barely in sight on the other side of the bay. We decided to run into Northport, a summer resort town on Northport Bay.

Leaving Northport early Monday morning, August twenty-fourth, we found a very gentle north wind blowing, clear skies, and every indication favorable for getting across Grand Traverse Bay. Shoving off at 7:30 we slid through about five miles of glassy smoothness out of Northport Bay, and go well out into Grand Traverse Bay before we began to encounter any appreciable roughness. Then the gentle ripples began to assume the proportions of choppy little waves, which gradually increased in size until we encountered what might be termed average English Channel weather. Taking the weather quartering on our starboard beam and astern, we wallowed and flopped along on a yawing course for Fisherman's Island, a little snag of land sticking up out of the bay about ten miles south of Charlevoix.

At noon we poked the nose of Transcontinental between the Charlevoix Harbor pierheads, and put-putted up the channel to the United States Coast Guard Station. Leaving the boat there in care of Captain Partridge, commander of the station, we went uptown for lunch.

|

| Library of Congress image of Charlevoix Harbor around 1900 |

The familiar accusation that Chicago running the lake out through the Drainage Canal has lowered the lake so boats can't get through Mud Creek was given as the reason the west end of the route being closed. The Secretary, however, said that if we were willing to make a portage of about three miles we could easily get through the rest of the way to Lake Huron over easily navigable and sheltered inland waters. Much as I detested portages, a portage of three miles seemed preferable to a possible delay of several days waiting for weather that would let us into the Straits of Mackinac. The Secretary also promised every possible cooperation, so I requested him to have a motor truck waiting for us when we arrived at Petoskey at four o'clock that afternoon.

With that arrangement completed we shoved off from the Coast Guard Station and headed up the lake around Big Rock Point and into Little Traverse Bay. This part of the trip was anything but smooth going. We got pummeled and pounded by the waves all the way, and when we got into Little Traverse Bay we found it not far behind its big brother, Grand Traverse Bay, for unadulterated, choppy wickedness in a breeze that was not blowing more than twenty miles an hour. However, the weather was dead astern of us, and despite yawing and floundering around we pulled in behind the Petoskey breakwater at exactly four minutes after four.

(The second half of this installment to be continued.)